PROJECT MANAGEMENT

A project is temporary in that it has a defined beginning and end in time, and therefore defined scope and resources.

And a project is unique in that it is not a routine operation, but a specific set of operations designed to accomplish a singular goal. So a project team often includes people who don’t usually work together – sometimes from different organizations and across multiple geographies.

The development of software for an improved business process, the construction of a building or bridge, the relief effort after a natural disaster, the expansion of sales into a new geographic market — all are projects.

And all must be expertly managed to deliver the on-time, on-budget results, learning and integration that organizations need.

Project management, then, is the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet the project requirements.

It has always been practiced informally, but began to emerge as a distinct profession in the mid-20th century.

Project management is the planning, organizing and managing the effort to accomplish a successful project. A project is a one-time activity that produces a specific output and or outcome, for example, a building or a major new computer system. This is in contrast to a program, (referred to a 'programme' in the UK) which is 1) an ongoing process, such as a quality control program, or 2) an activity to manage a number of multiple projects together.

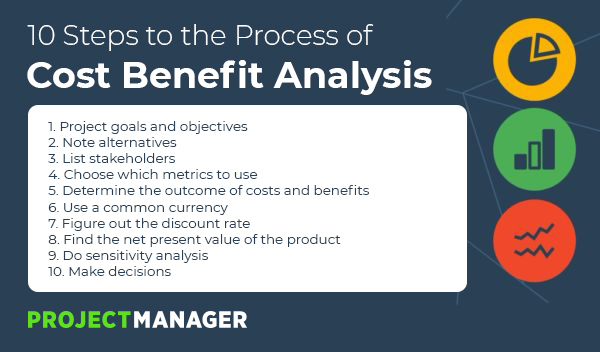

Project management includes developing a project plan, which involves defining and confirming the project goals and objectives, how they will be achieved, identifying tasks and quantifying the resources needed, and determining budgets and timelines for completion. It also includes managing the implementation of the project plan, along with operating regular 'controls' to ensure that there is accurate and objective information on 'performance' relative to the plan, and the mechanisms to implement recovery actions where necessary.

Projects often follow major phases or stages (with various titles for these), for example: feasibility, definition, planning, implementation, evaluation and realisation.

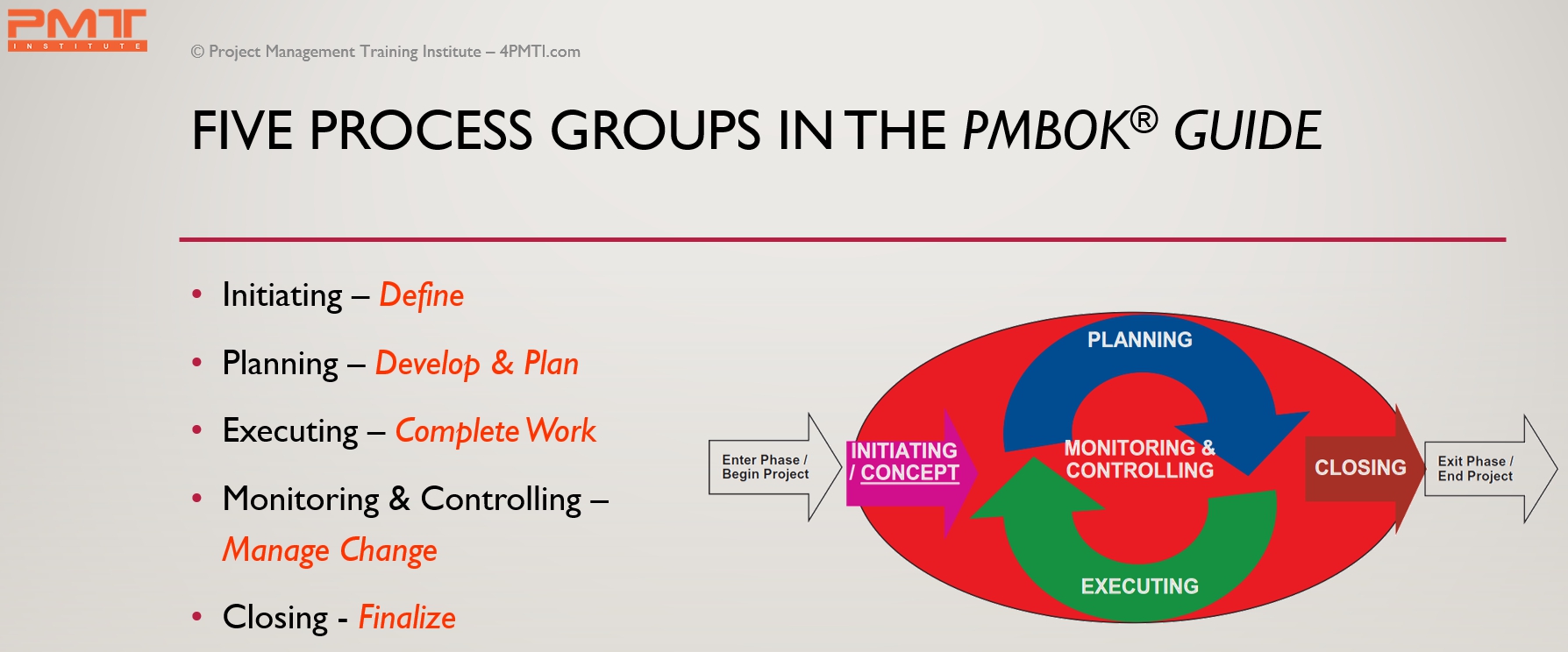

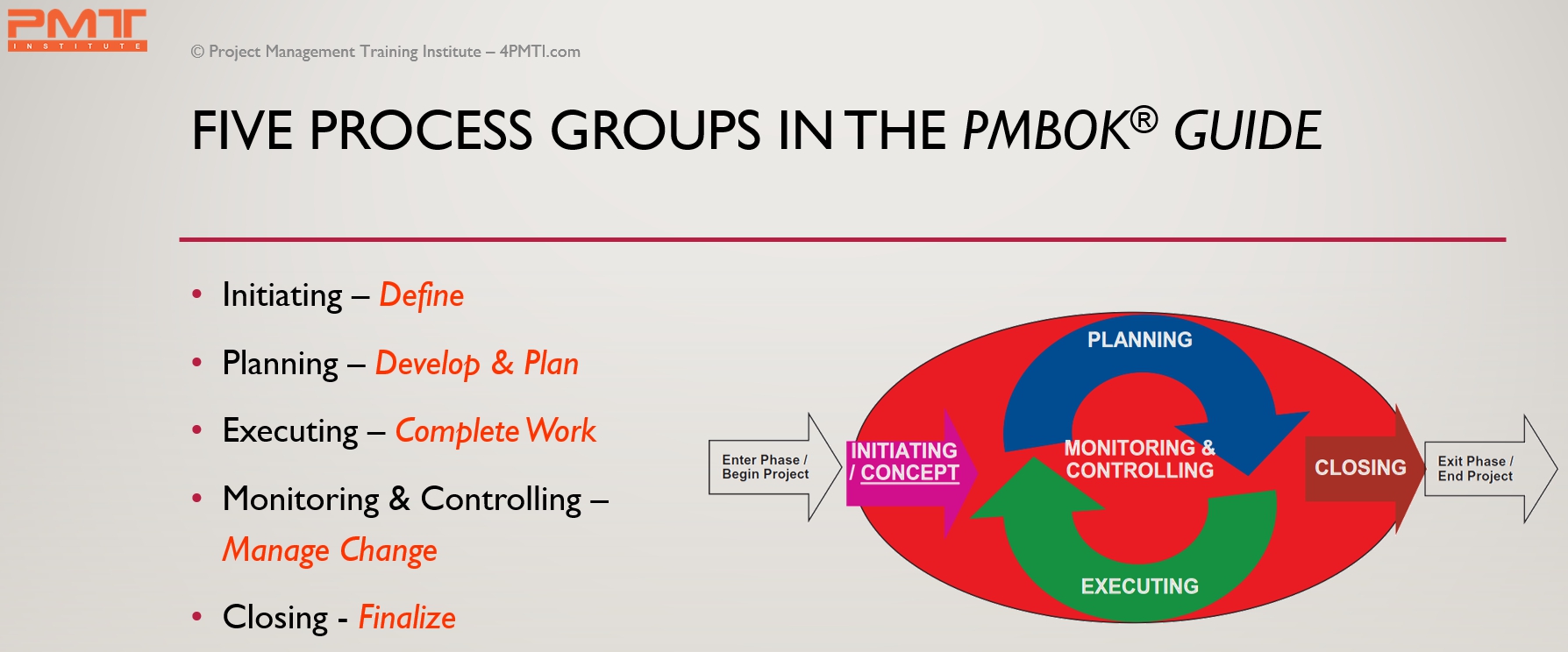

Project management processes fall into five groups:

- Initiating

- Planning

- Executing

- Monitoring and Controlling

- Closing

Project management knowledge draws on ten areas:

- Integration

- Scope

- Time

- Cost

- Quality

- Procurement

- Human resources

- Communications

- Risk management

- Stakeholder management

8 Steps to a Foolproof Project Plan

Step 1: Identify & Meet with Stakeholders

Project Stake holders

A stakeholder is anyone who is affected by the results of your project plan. That includes your customers and end users. Make sure you identify all stakeholders and keep their interests in mind when creating your project plan.

Meet with the project sponsors and key stakeholders to discuss their needs and expectations, and establish baselines for project scope, budget, and timeline. Then create a Scope Statement document to finalize and record project scope details, get everyone on the same page, and reduce the chances of costly miscommunication. Here's a Scope Statement Template to get you started.

Tip: Look beyond the stakeholders' stated needs to identify the underlying desired benefits. These benefits are the objectives your project should deliver.

Step 2: Set & Prioritize Goals

Once you have a list of stakeholder needs, prioritize them and set specific project goals. These should outline project objectives, or the metrics and benefits you hope to achieve. Write your goals and the stakeholder needs they address in your project plan so it's clearly communicated and easily shareable.

Tip: "But everything is important!" If you're having trouble prioritizing, start ranking goals based on urgency and importance, or check out these helpful decision making tips.

Step 3: Define Deliverables

Identify the deliverables and project planning steps required to meet the project's goals. What are the specific outputs you're expected to produce?

Next, estimate due dates for each deliverable in your project plan. (You can finalize these dates when you sit down to define your project schedule in the next step.)

Tip: Set firm milestones for essential deadlines and deliverables. You'll be able to track your progress once work begins to ensure you complete tasks on time and keep stakeholders happy.

Step 4: Create the Project Schedule

Look at each deliverable and define the series of tasks that must be completed to accomplish each one. For each task, determine the amount of time it will take, the resources necessary, and who will be responsible for execution.

Next, identify any dependencies. Do you need to complete certain tasks before others can begin? Input deliverables, dependencies, and milestones into your Gantt chart, or choose from the many online templates and apps available.

Add milestones

Use your list of deliverables as a framework for adding milestones and tasks that will need to be completed to accomplish the larger goal. Establish reasonable deadlines, taking into account project team members’ productivity, availability, and efficiency.

Think about your milestones within the SMART framework. Your goals should be:

- Specific: Clear, concise, and written in language anyone could understand.

- Measurable: Use numbers or quantitative language when appropriate. Avoid vague descriptions that leave success up to personal, subjective interpretation.

- Acceptable: Get buy-in from stakeholders on your goals, milestones, and deliverables.

- Realistic: Stretch goals are one thing, but don’t set goals that are impossible to achieve. It’s frustrating for your team and for your stakeholders, and might ultimately delay your project because accomplishing the impossible usually costs more and takes longer.

- Time-based: Set concrete deadlines. If you have to alter deadlines associated with your milestones, document when and why you made the change. Avoid stealth changes—or editing deadlines without notifying your team and relevant stakeholders.

Tip: Involve your team in the planning process. The people performing the work have important insights into how tasks get done, how long they'll take, and who's the best person to tackle them. Draw on their knowledge! You'll need them to agree with the project schedule and set expectations for work to run smoothly.

Step 5: Identify Issues and Complete a Risk Assessment

No project is risk-free. Crossing your fingers and hoping for the best isn’t doing you any favors. Are there any issues you know of upfront that will affect the project planning process, like a key team member's upcoming vacation? What unforeseen circumstances could create hiccups? (Think international holidays, back ordered parts, or busy seasons.)

When developing a project plan, consider the steps you should take to either prevent certain risks from happening, or limit their negative impact. Conduct a risk assessment and develop a risk management strategy to make sure you're prepared.

Tip: Tackle high-risk items early in your project timeline, if possible. Or create a small "time buffer" around the task to help keep your project on track in the event of a delay.

Step 6: Create a budget

Attached to your list of milestones and deliverables should be information about the project cost and estimated budget. Resist the urge to assign large dollar amounts to big projects without identifying exactly how the money is intended to be spent. This will help your team understand the resources they have to work with to get the job done. When you’re setting your initial budget, these numbers might be ranges rather than absolutes.

For certain items, you might need to get quotes from a few different vendors. It can be helpful to document the agreed upon project scope briefly in your budget documentation, in case you end up needing to make changes to the larger project based on budgetary constraints, or if your vendor doesn’t deliver exactly what you expected.

Step 7 : Present the Project Plan to Stakeholders

Explain how your plan addresses stakeholders' expectations, and present your solutions to any conflicts. Make sure your presentation isn't one-sided. Have an open discussion with stakeholders instead.

Next, you need to determine roles: Who needs to see which reports, and how often? Which decisions will need to be approved, and by whom?

Make your project plan clear and accessible to all stakeholders so they don’t have to chase you down for simple updates. Housing all project plan data in a single location, like a collaboration tool, makes it easy to track progress, share updates, and make edits without filling your calendar with meetings.

Communicate clearly. Make sure stakeholders know exactly what's expected of them, and what actions they need to take. Just because it's obvious to you doesn't mean it's obvious to them!

Not looking forward to having an open discussion with your stakeholders? Here are some strategies to arm yourself against difficult stakeholders to keep the project planning process moving forward.

Tip: If your plan or schedule doesn’t align with stakeholders' original expectations, communicate that now to avoid any nasty surprises or tense conversations down the line.

Step 8: Set progress reporting guidelines

These can be monthly, weekly, or daily reports. Ideally, a collaborative workspace should be set up for your project online or offline where all parties can monitor the progress. Make sure you have a communication plan—document how often you’ll update stakeholders on progress and how you’ll share information—like at a weekly meeting or daily email.

Use the framework you set up when you identified your milestones to guide your reports. Try not to recreate any wheels or waste time with generating new reports each time you need to communicate progress. Keep in mind that using a project management software like Basecamp can keep stakeholders in the loop without cluttering up your inbox, or losing conversations in long Slack chats.

The secret to effective project planning and management is staying organized and communicating well with your team and stakeholders. Whether you decide to use project management software or not, think about where and how you store all the materials and resources that relate to your project—keep everything in one place if you can.

There are a range of different methodologies which are often applied to project management, with the three most commonly considered being PMBOK, PRINCE2 and Agile. If you're trying to weigh up what are the pros and cons of PMBOK versus PRINCE2 versus something like Agile, you may find it useful to consider them in context with the project that you're undertaking, as well as comparing one to the other.

PMBOK - pros and cons

PMBOK is short for Project Management Body of Knowledge. Users of this system find that it has more substantial frameworks for contract management, scope management and other aspects which are arguably less robust in PRINCE2. However, many users of PMBOK find that they are not entirely happy with the way this system limits decision making solely to project managers, making it difficult for handing over aspects of the management to other parties and senior managers. With PMBOK, the project manager can seemingly become the primary decision maker, planner, problem solver, human resource manager and so on.

PRINCE2 - pros and cons

PRINCE2 stands for Projects in a Controlled Environment and this is a project management program that shares more of the functional and financial authority with senior management, not just the project manager. This program has a focus on aiding the project manager to oversee projects on behalf of an organisation's senior management. On the pros side, PRINCE2 provides a single standard approach to the management projects, which is why many government and global organisations prefer this option. It is also favoured because of its ease of use, which makes is easy to learn, even for those with limited experience. On the downside, there are users who feel that PRINCE2 misses the importance of “soft skills” that should be a focus for a project manager.

Agile - pros and cons

Agile is a more distinct program from PMBOK and PRINCE2. The Agile methodology is more flexible, making it better able to produce deliverables without the need for substantial changes and reworking. Tasks can be broken down into smaller stages and this allows for substantial risk reduction through earlier assessment, testing and analysis. The main drawback of Agile is that if it is not fully grasped, the methodology could lead to unattainable expectations.

If you're interested in comparing PMBOK vs PRINCE2 vs Agile and you're wondering about the pros and cons there are several answers. Each of these has it distinct differences. If you're project needs to be small and adaptable, then Agile may be the answer. If the project manager needs to be the sole decision maker, then PMBOK could be preferable and so on. Each project manager will form different opinions and they may even change their mind on which is best based upon changes from one project to the next.

PERT vs. CPM

PERT and CPM are two quite famous managerial techniques.

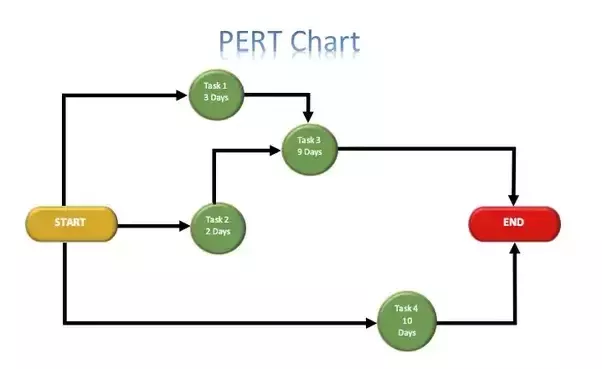

PERT is an abbreviation of Program Evaluation and Review Technique. It has been developed originally for the United States Navy as part of the Polaris program as a 16 mathematical method for defining the minimum time for completion of a complex project.

So, the PERT main objective is to provide a tight and sufficient control of the management of complex projects through an integrated system of forced planning and evaluation. Thus, adoption of PERT in a company streamlines production, connects it with economic objectives and optimize the amount of men and material.

PERT is composed of four features : Critical path analysis; Program status evaluation; Slack determination (denotes how much an activity can be delayed beyond its earliest start date, without causing any problems in the completion of the project by its deadline) and Simulation.

In the PERT method, Tasks are connected in a network and each Task has tempo properties such as, the most pessimistic, the most optimistic and the most likely durations.

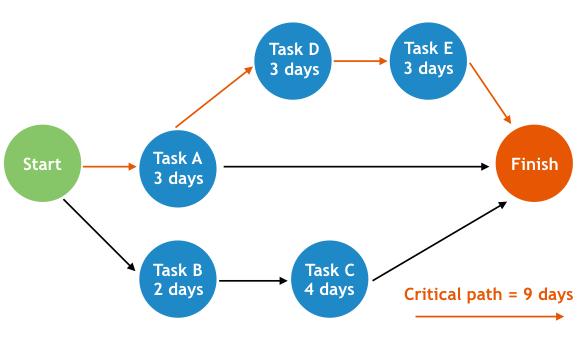

CPM is an abbreviation of Critical Path Method, and similarly to PERT aims in facilitating companies' management system to achieve corporate objectives.

Implementation of CPM requires: Identification of the activities and their sequence; Composition a network diagram; Estimation of the completion time for each activity; Identification of the critical path and Calculation of the total project period.

The main concern of CPM is cost optimization which directly influences the project deadline. Thus, activity duration may be estimated with a fair degree of accuracy and no probabilistic model is used.

So, in summary:

Both PERT and CPM are managerial techniques which aim at achieving companies' goals, but in case of PERT, uncertainty component is accepted and states as a part of the system.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PERT AND CPM:

1. PERT is event oriented whereas CPM is activity oriented. In simple words, in PERT network interest is focused upon start or completion of events and not on activities themselves.

2. In CPM network no allowance is made for uncertainties in the duration of time involved whereas in PERT network uncertainty is considered.

3. In PERT, time is not related to cost whereas in CPM the object is to develop an optimum time cost relationship. However, PERT has since been extended in this direction and the line dividing PERT/CPM is gradually fading out.

4. In CPM duration of activity is estimated with a fair degree of accuracy. In PERT duration of activities are not so accurate and definite.

5. In CPM both time and cost can be controlled during planning. Pert is basically a tool for planning.

6. PERT is used in research and development project, basically for non-repetitive type projects.

CPM is widely used in construction projects.

ADVANTAGES OF PERT AND CPM:

The various advantages of PERT/CPM methods are summarized below.

1. In the network technique of planning and scheduling, one is compelled to examine the complete project in advance and interact with everyone who is to be involved in the project thereby evolving a workable plan of the project. One is also forced to decide upon the extent of splitting of the project into smaller activities and to establish logical relationship between different activities.

2. It helps in dividing activities function wise and responsibility wise which makes it possible to co-ordinate the works of different agencies involved in the completion of the project.

3. It enables one to determine reasonably correct schedule for the completion of different events and the project as a whole based on the availability of resources (i.e. men, material, money and machines etc.)

4. It permits one to take advance actions and timely decisions to reduce delays in completion of different events.

5. It permits greater flexibility in having optimum utilization of resources thereby effecting economy.

6.

It identifies activities critical to different stages of projects

completion which in turn enables the management to pay greater attention

to fewer activities instead of concentrating on all activities at all

times with equal emphasis.

7.

It enables one to exercise effective control on the project by way of

periodic review and to adopt timely corrective measures to minimize

slippage in the completion of the project.

Comparison

Chart

Basis

for Comparison

|

PERT

|

CPM

|

Meaning

|

PERT is a project management

technique, used to manage uncertain activities of a project.

|

CPM is a statistical technique of

project management that manages well defined activities of a project.

|

What is it?

|

A technique of planning and

control of time.

|

A method to control cost and time.

|

Orientation

|

Event-oriented

|

Activity-oriented

|

Evolution

|

Evolved as Research &

Development project

|

Evolved as Construction project

|

Model

|

Probabilistic Model

|

Deterministic Model

|

Focuses on

|

Time

|

Time-cost trade-off

|

Estimates

|

Three time estimates

|

One time estimate

|

Appropriate for

|

High precision time estimate

|

Reasonable time estimate

|

Management of

|

Unpredictable Activities

|

Predictable activities

|

Nature of jobs

|

Non-repetitive nature

|

Repetitive nature

|

Critical and Non-critical

activities

|

No differentiation

|

Differentiated

|

Suitable for

|

Research and Development Project

|

Non-research projects like civil

construction, ship building etc.

|

Crashing concept

|

Not Applicable

|

Applicable

|

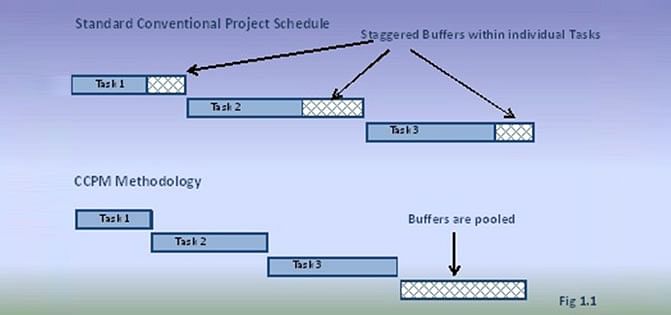

Critical Chain Project Management

Critical Chain Project Management was developed and publicized by Dr. Eliyahu M. Goldratt in 1997. Followers of this methodology of Project Management claim it to be an alternative to the established standard of Project Management as advocated by PMBOK® and other standards of project management. In this article, we’ll provide a brief overview of the principles of Critical Chain Project Management and its applicability to managing projects across all organizations and verticals.

The Critical Chain Method has its roots in another one of Dr. Goldratt’s inventions: the Theory of Constraints (TOC). This project management method comes into force after the initial project schedule is prepared, which includes establishing task dependencies. The evolved critical path is reworked based on the Critical Chain Method. To do so, the methodology assumes constraints related to each task.

A few of these constraints include:

- There is a certain amount of uncertainty in each task.

- Task durations are often overestimated by the team members or task owners. This is typically done to add a safety margin to the task so as to be certain of its completion in the decided duration.

- In most cases, the tasks should not take the time estimated, which includes the safety margin, and should be completed earlier.

- If the safety margin assumed is not needed, it is actually wasted. If the task is finished sooner, it may not necessarily mean that the successor task can start earlier as the resources required for the successor task may not be available until their scheduled time. In other words, the saved time cannot be passed on to finish the project early. On the other hand, if there are delays over and above the estimated schedules, these delays will most definitely get passed on, and, in most cases, will exponentially increase the project schedule.

With the above assumptions, the Critical Path Methodology of project management recommends pooling of the task buffers and adding them at the end of the critical path:

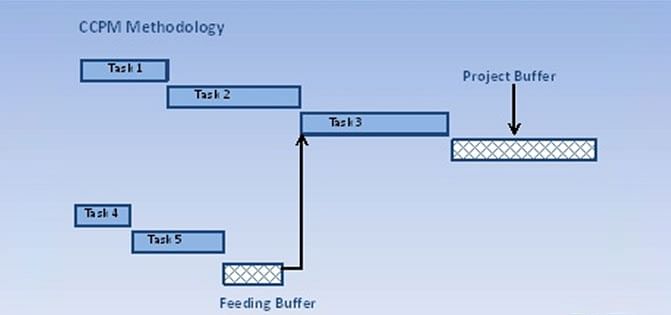

Critical Path project management defines three types of buffers:

- Project Buffer: The total pooled buffer depicted in the image above is referred to as the project buffer.

- Feeding Buffer: In a project network, there are path/s which feed into the critical path. The pooled buffer on each such path represents the feeding buffer to the critical path (depicted in the image below), resulting in providing some slack to the critical path.

- Resource Buffer: This is a virtual task inserted just before critical chain tasks that require critical resources. This acts as a trigger point for the resource, indicating when the critical path is about to begin.

As the progress of the project is reported, the critical chain is recalculated. In fact, monitoring and controlling of the project primarily focuses on utilization of the buffers. As you can see, the critical chain method considers the basic critical path based project network and schedule to derive a completely new schedule.

The critical path project management methodology is very effective in organizations which do not have evolved project management practices

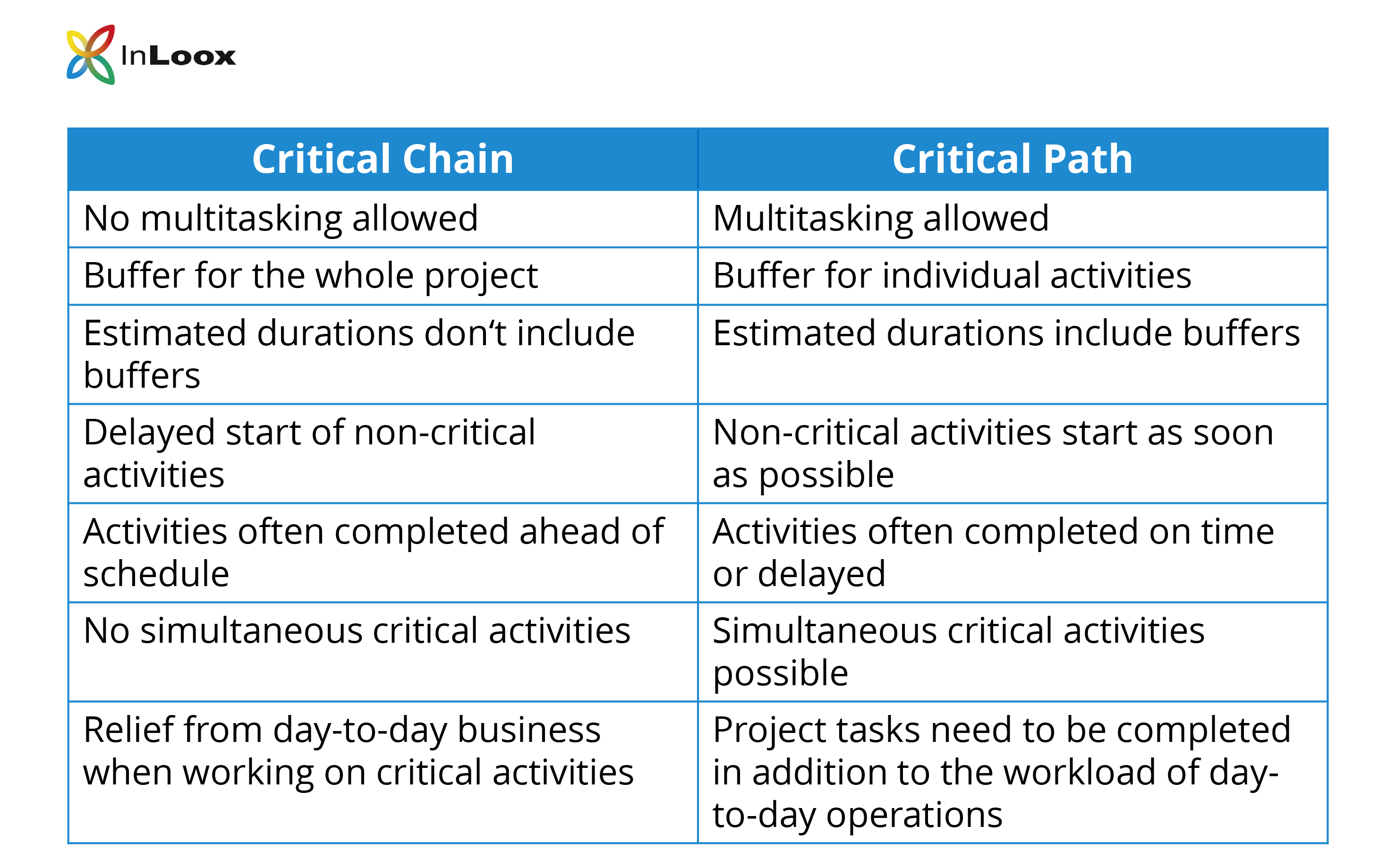

Critical chain vs critical path method

Of all the project management methods, Critical

Chain and Critical Path are frequently confused. Nevertheless, there is a

world of difference between the two approaches.

The Critical Chain Model (derived from the Theory

of Constraints) has a resource focus, whereas Critical Path is task

order focused.

Given the key attributes of change projects, such

as poorly defined project tasks, multi-stakeholder environment etc,

Critical Chain Modelling best addresses the inherent uncertainty

associated with change and human behaviours, and consequently keeps

projects better under control.

The Critical Chain Method addresses the human response to executing

multiple tasks and divides the work into natural work streams.

Critical Path, on the other hand, concentrates on

tasks in terms of resource and time efficiencies, causing schedule risk.

4 Tips for Monitoring (and Measuring) Projects

1. Defining Success

First, you need to establish what success means to you. Is it:

- A project that delivers on time?

- Happy customers?

- Meeting your quality targets?

- Finishing under budget (or at least on budget)?

- Something else?

In reality, it’s likely to be a combination of all those things but something will jump out as the most important. Pick the top two or three things that are your “must haves.” Discuss them with your team so that you agree how you are going to define success on this project.

Then write them up somewhere so that you can look at them again and again.

You’ll want to look at them at the end of the project, too, as your success criteria will help inform whether or not your project has been a success in the eyes of the stakeholders.

2. Choose Your Metrics

Now that you know what is important to you and what the important success criteria are for this project, you need to come up with some metrics that help you measure those. This is what will let you track your projects.

Here are some examples:

Schedule Variance Metric

For example, if it’s critical that you hit your deadline because the product must be launched before a certain date, then you’ll definitely want to measure how you are doing against your project plan and whether you are making progress as you expected.

Cost Variance Metric

If staying on budget is more important, then you’ll choose metrics that show you how much you have spent and whether that lines up with what you thought you’d be spending at this point.

Stakeholder Satisfaction Metric

When keeping your stakeholders happy is the most essential thing for the team, then you’ll have to find a way to measure customer satisfaction on an ongoing basis. That’s easier to do than it sounds: you can get quite scientific about it with a simple survey.

Identify the metrics that go hand in hand with the success criteria that you want to track. On small projects you might just have one main measure. On larger projects you’ll have a selection of metrics that give you a bigger picture view. Whatever you decide is fine because you’ve already aligned your metrics to what is important.

3. Measure Your Progress

As the project moves forward you can track your performance. Use the metrics that you have chosen. These link directly to how you are measuring success, so you’ll be able to see how you are doing at a glance and whether you are on track to hit your targets.

The easiest way to do this is to use a dashboard that pulls real-time information from the data in your project management system. You’ll only have one screen to look at. Set it up once and then leave it to run so it always shows you the most up-to-date picture of what is going on. You’ll be able to drill down into the detail if you see something that looks a bit strange.

You’ll want to look at (and act on) the data that the metrics give you at least once a month. On smaller, agile projects, you should be reviewing status a lot more frequently than that: at least once a week but go more frequent even than that if it makes sense.

4. Refine and Improve

As with all things on projects (and in life) we never rest when we could improve. There are two sets of improvements to consider as you go forward.

First, are your metrics the right ones? Once you’ve been tracking them for a while, you’ll know whether they are telling you the data that you need to make decisions. If they aren’t, it’s time to look at what else you could track instead that would give you better information about how the project is doing.

Second, how easy is it to get to the data? If it takes you a long time to calculate the results and present them to share with the team, then your project tracking is slowing you down. Go back to your data capture and reports or dashboards and tweak them so it’s more efficient to get and analyze the data.

These four steps are all you need to set up good quality project monitoring on your projects and track them like a pro. Soon you’ll be able to see how your project is performing at a glance, and step in to correct the course when you have to.

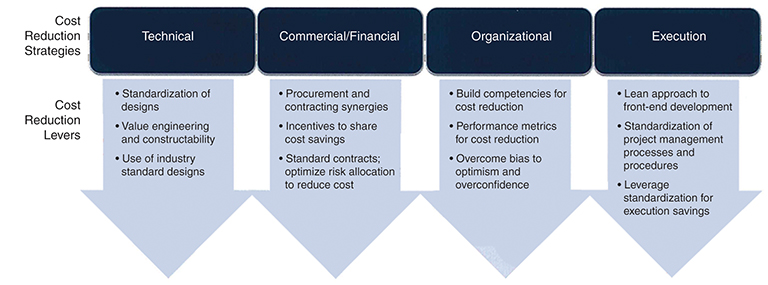

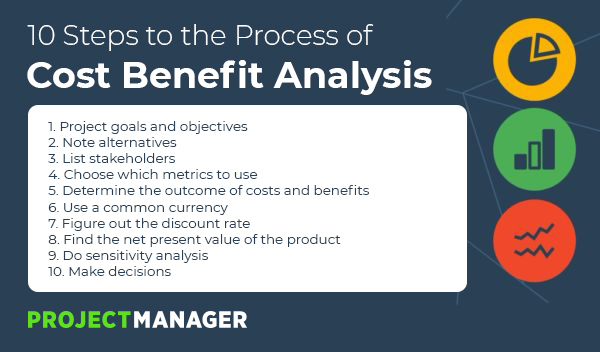

Project Budgeting and Cost Control

Cost management is concerned with the process of planning and controlling the budget of a project or business. It includes activities such as planning, estimating, budgeting, financing, funding, managing, and controlling costs so that the project can be completed within the approved budget. Cost management covers the full life cycle of a project from the initial planning phase towards measuring the actual cost performance and project completion. This article will explain the different steps or processes in Project Cost Management, in line with methods such as the PMBOK.

Step 1: Resource planning

In the initial phase of a project the required resources to complete the project activities need to be defined. Work Breakdown Structures (WBS) and historical information of comparable projects can be used to define which physical resources are needed. You can think of the required time, material, labor, equipment, etc. Once the resource types and quantities are known the associated costs can be determined.

Step 2: Cost estimating

Several cost estimating methods can be applied to predict how much it will cost to perform the project activities. The choice for the estimation method depends on the level of information available. Analogous estimating using the actual cost of previous, similar projects can serve as a basis for estimating the current project. Another option is to use parametric models in which the project characteristics are mathematically represented. Estimates can be refined when more information becomes available during the course of a project. Eventually this results in a detailed unit cost estimate with a high accuracy. Remaining uncertainties in estimates that will likely result in additional cost can be covered by reserving cost (e.g. using escalation and contingencies).

Step 3: Cost budgeting

The cost estimate forms together with a project schedule the input for cost budgeting. The budget gives an overview of the periodic and total costs of the project. The cost estimates define the cost of each work package or activity, whereas the budget allocates the costs over the time period when the cost will be incurred. A cost baseline is an approved time-phased budget that is used as a starting point to measure actual performance progress.

Step 4: Cost control

Cost control is concerned with measuring variances from the cost baseline and taking effective corrective action to achieve minimum costs. Procedures are applied to monitor expenditures and performance against the progress of a project. All changes to the cost baseline need to be recorded and the expected final total costs are continuously forecasted. When actual cost information becomes available an important part of cost control is to explain what is causing the variance from the cost baseline. Based on this analysis, corrective action might be required to avoid cost overruns.

Dedicated cost control software tools can be valuable to define cost control procedures, track and approve changes and apply analysis. Furthermore, reporting can be enhanced and simplified which makes it easier to inform all stakeholders involved in the project.

Managing Project Costs

Cost management is a way of managing project cost, which includes estimating project costs. Therefore, the first thing you want to do is to get an estimation of all your costs at the task level.

Once you have those figures, you can move onto the next step, which is developing a project budget. You want to baseline all the costs and create a set of actions that will keep you on track.

All of these initial steps are taken to control spending for the project. In order to track project costs throughout the project, consider making a template, or use our free project budget template. Once you have a template, start by collecting the labor, how long each task will take, the hourly rate of each team member, material costs and all units of measurement.

Other costs to measure include travel, equipment and space expenses. There are other fixed and miscellaneous costs, of course, and you want to note them again at the task level. Once you have your budgeted amount, you can track it as the project progresses.

Some project costs are easier to collect than others. Labor, consulting fees, raw materials, software and travel are considerably simpler to chart than other costs that might change.

These more difficult costs include such things as telephone charges, office space, office equipment, general administrative costs and company insurance.

Tips for Managing Project Cost

Before Jennifer finished her tutorial, she offered some tips to keep in mind as you’re working on managing your project costs.

- Plan for Inflation: Pricing is not set in stone, and any good budget is going to take this into account by allowing for a range of costs.

- Account for Natural Disasters or Potential Events: Expect the unexpected might sound silly, but you must have room in your budget for a weather event, personal issue or some other unknown that will delay the project.

- Other Unexpected Costs: Not all unexpected costs are random. There can be legal issues, penalties associated with the project or unexpected labor costs, all of which you can’t budget for, but can prepare your budget for.

- Track in Real-Time: Having software to monitor the budget as you execute the project is key for managing costs. However, if you’re looking at data that is not current, you won’t be able to act swiftly enough to resolve issues. Therefore, you want to have software with real-time data tracking.

- Respond Promptly: Regardless of how you discover a discrepancy in your project cost, you must act immediately. The longer you wait, the more money is wasted.

- Size Accordingly: Some people think smaller projects don’t need project cost management. But small or large, you’ll want to manage costs.

Pro-Tip: In order to best manage project costs, you have to know your project inside and out. The best way to do that is at the start of the project by creating a thorough project charter.

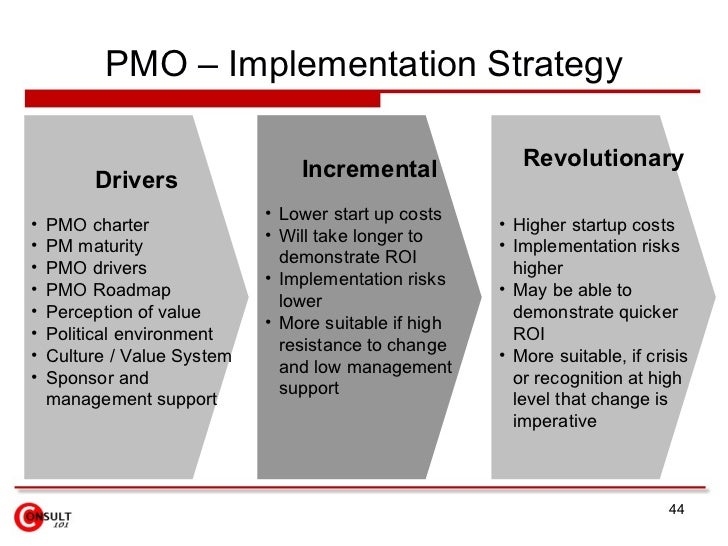

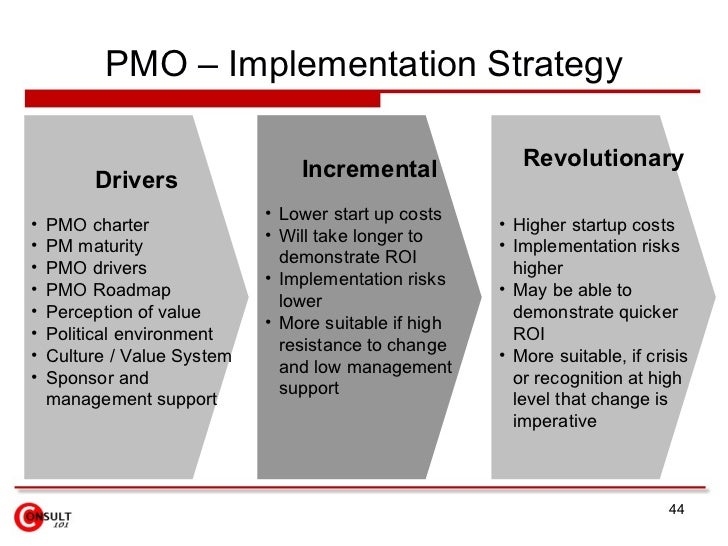

PMO Charter

The purpose of PMO charter

The purpose of a project charter is to define the scope, objectives and participants of a project. The same is equally true of a PMO charter, it defines the scope of the PMO i.e. oversight of all change programmes over £5 million of spend, the objectives of a PMO i.e. promote the use of standard project delivery methodology to improve the probability of success and participants i.e. define the PMO organisation structure and name role holders.

A PMO charter is simply a document, normally designed in a word processor or presentation. The document will contain words and diagrams to clearly articulate the scope, objectives and participants of the PMO. It is important that the document is direct and to the point. This helps to ensure that the key points are easy to understand and, does not discourage people from reading (a long document may have ‘thud’ factor but many will be put-off from reading, important points will be missed and it could be viewed as being bureaucratic).

The key points to cover in a PMO charter is:

- Background – set the context and reason for setting up the PMO

- Scope – make it clear what services the PMO will provide (“what it will do”). It also is worth capturing specific services that will not be provided (especially if they are what may be expected).

- Organisation Structure – explain how the PMO is structured and who covers each role.

- Engagement Model – document how the PMO will engage with projects and stakeholders.

- Services – provide more information on the services that will be provided by the PMO.

You should also add details of any specific service or responsibility over and above the points listed above if it is important and / or required by your organisation. Remember, the PMO is designed to serve the needs of your organisation.

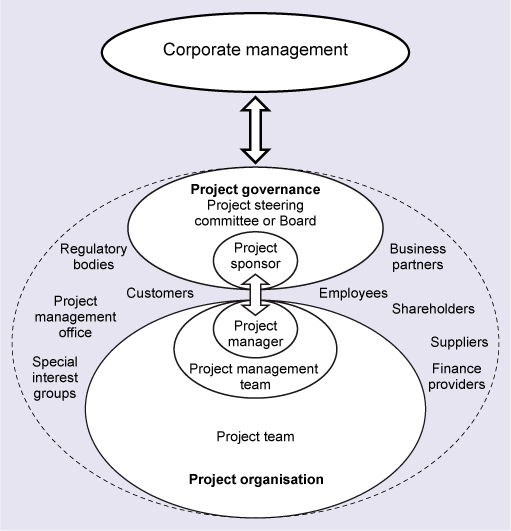

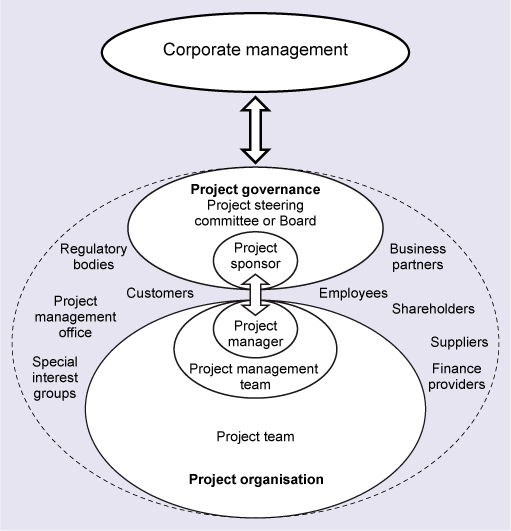

Project Governance

The governance of a project is much like the governance of an organisation.

Project governance is:

The set of policies, regulations, functions, processes, and procedures and responsibilities that define the establishment, management and control of projects, programmes or portfolios.

Some projects are run solely by the project manager. Where this is appropriate for the type of project, and the organisation, it is not necessary to have all the aspects of governance that are discussed in this section.

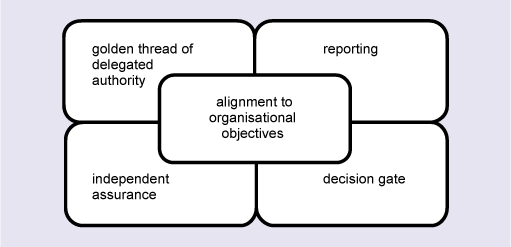

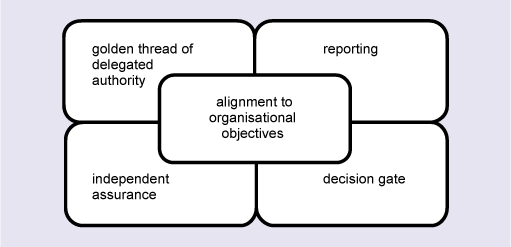

Below Figure illustrates good governance as explained by Murray (2011). Murray’s explanation is compatible with the APM definition but focuses just on projects rather than including programmes or portfolios too. He gives five elements, based on project governance or project management governance, with emphasis on alignment to organisational objectives as a central aspect of good governance. He uses the term ‘decision gate’ in place of a stage gate or approval gate.

Essential elements of good project governance

- Alignment to organisational objectives means that the projects undertaken by an organisation should be able to demonstrate, in the business case, the contribution to the organisation’s objectives. With this contribution clearly stated then the project context is clear and governance of the project can ensure that the project is focused on the outcome rather than activities.

- The golden thread of delegated authority is a direct chain of accountability. Within this chain each person needs to know what their authority is and what needs to be referred to a higher level of authority within the chain.

- Reporting – those to whom responsibilities have been delegated should periodically report on progress. In addition to period reporting, additional reports need to be made if the person with delegated responsibility is unable to fulfil that responsibility, or if conflicts of interest arise.

- Independent assurance is a counterbalance to self-reporting, and is an independent check of the structures and processes to review whether the objectives will be met.

- Decision gates – at specified points in the project life cycle − provide formal points of control where a decision is made to grant or renew authority for the project to continue.

The strategic management of an organisation identifies and implements the long-term goals of that organisation. The choice of projects (in programmes or portfolios if appropriate), and carrying them out successfully, is part of the organisation’s activities to achieve those goals. Therefore the organisation, at the strategic level, typically needs to establish the governance structures for the management of projects. Organisations have corporate governance, of which project governance is a subset. Project management incorporates those aspects of project governance that are at the project level, as well as managing the detail of the project.

The APM identifies the following ways in which good governance can be demonstrated:

- The adoption of a disciplined life cycle governance that includes approval gates at which viability is reviewed and approved.

- Recording and communicating decisions made at approval gates.

- The acceptance of responsibility by the organisation’s management board for project governance.

- Establishing clearly defined roles, responsibilities and performance criteria for governance.

- Developing coherent and supportive relationships between business strategy and projects.

- Procedures that allow a management board to call for an independent scrutiny of projects.

- Fostering a culture of improvement and frank disclosure of project information.

- Giving members of delegated bodies the capability and resources to make appropriate decisions.

- Ensuring that business cases are supported by information that allows reliable decision making.

- Ensuring that stakeholders are engaged at a level that reflects their importance to the organisation and in a way that fosters trust.

- The deployment of suitably qualified and experienced people.

- Ensuring that project management adds value.

Contract and Vendor Management

Contract Management

Extensions of existing contracts (including SLAs/KPIs) often occurs automatically, without anyone monitoring whether the contract terms are still applicable and relevant. . Updating your existing contacts at such moments could potentially result in benefits. For example, you can choose to consolidate contracts; this allows you to negotiate higher discounts and/or customization requirements. In cooperation with you, Witscraft will make sure existing contracts are optimised from both an efficiency and effectivity perspective.

Vendor Management

Vendor Management is a separate area which works in parallel

with Procurement (supplier selection and legal agreements) and Contract

Management (utilization). On a strategic level, Vendor Management deals with

the question which of the (core) suppliers are in the best position to provide

your business with products /services now and in the future. Innovation,

knowledge, pro-activity and financial stability are essential components. A

supplier who suddenly disappears at a critical stage or appears incapable could

cost you. Vendor Management is a continuous process where suppliers and

customers regularly interact with each other.

Procurement Process

Step 1: Conduct an internal needs analysis

To begin, you’ll need to benchmark current performance and then identify needs and targets before developing a procurement strategy. This involves the collection of several different types of data.

The purpose for collecting initial data is to benchmark current performance, resources used, costs for all the departments/functions in the organization, and current growth projections.

Step 2: Conduct an assessment of the supplier’s market

In this step, the strategic procurement team identifies potential countries that are feasible sources of the required raw materials, components, finished goods or services. If there are specific requirements, it may limit the number of countries that are suitable. For instance, if one of the raw materials used by the organization can only be found in one country, then options are much narrower. For manufactured products, there will be a much wider range of potential countries from which to select. Services may be limited by the technological requirements of the organization.

Step 3: Collect supplier information

It is important for a company to select suppliers carefully. A supplier’s inability to meet selection criteria can result in significant losses for the organization. The business reputation and performance of the supplier must be evaluated, and financial statements, credit reports, and references must be checked carefully. If possible, the organization should arrange to inspect the supplier’s site and talk to other customers about their experiences with the supplier. The use of agents, who are familiar with the markets and stakeholders, can also be beneficial to this process.

Organizations may select more than one supplier to avoid potential supply disruptions as well as create a competitive environment. This strategy is also effective for large multinational organizations and allows for centralized control, but more regional delivery.

Step 4: Develop a sourcing/outsourcing strategy

Based on the information gathered in the first three steps, an organization can develop a sourcing/outsourcing strategy. The following are examples of sourcing strategies:

Direct purchase: Sending a Request for Proposal (RFP) or a Request for Quote (RFQ) to select suppliers.

Acquisition: Purchasing from a desirable supplier.

Strategic partnership: Entering into an agreement with a selected supplier.

Determining the right strategy for you will depend on the competitiveness of the supplier marketplace and the sourcing/outsourcing organization’s risk tolerance, overall business strategy and motivation for outsourcing.

Step 5: Implement the sourcing strategy

Sourcing strategies that involve acquisition or strategic partnerships are major undertakings. In these cases, suppliers are likely to have the following characteristics:

Involvement in activities core to the buyer, e.g. supply limited raw material for core product, access to highly confidential proprietary knowledge

One of a limited number of available suppliers with specific equipment/ technology and skilled labour pool

Part of the broader business strategy

For a direct purchase, organizations may begin with an Expression of Interest (EOI), prepare an RFP or RFQ, and solicit bids from identified potential suppliers as part of a competitive bidding process. The RFP should include:

detailed material

product or service specifications

delivery and service requirements

evaluation criteria

pricing structure;

and financial terms.

Step 6: Negotiate with suppliers and select the winning bid

The strategic procurement team must evaluate responses from suppliers and apply its evaluation criteria.

Bidding suppliers might request additional information in order to make the most realistic bid, and the organization should supply this information to all bidders and enable them to respond to the new information before making a final decision.

The strategic procurement team will then evaluate the received proposals, quotes, or bids, and use the selection criteria and a process to either shortlist bidders to provide more detailed proposals (if reviewing EOIs) or select a first and second successful bidder (if reviewing RFPs or RFQs).

After the evaluation process is complete, the strategic procurement team will enter contract negotiations with the first selected bidder.

Step 7: Implement a transition plan or contractual supply chain improvements

Winning suppliers should be invited to participate in implementing improvements.

A communication plan must be developed and a system for measuring and evaluating performance will need to be devised using measurable Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

This is especially true in the early stages of using a new supplier.

Transition plans are especially important when switching suppliers.

Contractual Supply Chain Improvements

When bringing on new suppliers, it is necessary to transfer information and establish linkages to logistics and communication systems, provide training and even specific physical assets, if required. The implementation of these transfers takes time and expertise to set and start up. Expectations during this time frame should be agreed upon during contract negotiations with time frames for full operations and deliveries.

Transition Plans

The transition from in-house provision of services to an outsourced service provider can be one of the riskier aspects of global outsourcing of services. How the transition to the outsourced service is handled and how it is perceived by staff and the public are very important. Transparency and preparation are key to this aspect of the sourcing strategy.

These simple steps will Project Management team develop and implement a strategic procurement plan.

Project Financing & Funding Alternatives

Project finance arrangement

A project finance

arrangement is a structured finance scheme based on the long-term cash-flows

generated by an enterprise incorporated for an isolated project, taking as

collateral said enterprise’s assets. The truly differentiating element of a

project finance arrangement is that it is structured based on the long-term

predictability of its cash flows in accordance with a structure of fixed

contracts with its customers, suppliers, market regulators, etc.

These characteristics

are usually linked to companies that are active in the infrastructure, energy,

renewable or utilities sectors, to name a few, engaging in the development of

projects that require an especially costly initial investment and which are

depreciated over very long periods of time, such as such as roads, power

plants, vehicle park lots, airports, wind farms, refineries, etc.

Advantages and disadvantages

Revenue

stability and predictability is precisely what makes it possible to consider

financing structures subject to maturity and leveraging terms that exceed the

terms that a corporate structure with a comparable credit rating could ever opt

to. The appeal of longer terms and the higher volume of the loan offset the

potential drawbacks of project finance structures, such as higher costs and more

complex and lengthier closure processes.

In

terms of financing deadlines, they can be extended considerably, up to 30 years

for the highest-quality risks. Also, leveraging can reach levels impossible to

match in corporate financing operations, with some cases exceeding a 90:10

Debt-Capital ratio.

Project Recovery Methods

- To Save or Not to Save? – Read any article on the Internet about project recovery strategies and the first tip you’ll probably find is to ask yourself if the project can be saved. In the world of project management, there are many methodologies utilized, so to find out if a project is worth saving often relies on what method you’re using. A 5S, Lean Six Sigma or Agile project could be saved simply based on the phases used—meaning not every element is a total waste. On the other hand, if you’re using another methodology that requires lengthy stages, many resources, and not enough support, you may want to just let the ship sink and start again. If you choose to let the ship sail unfinished, keep in mind that you’ll most likely have a legal and binding contract with your client so you may have to redo the project for free.

- PMI Strategies – Within PMI’s Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), there are real steps that cover project recovery methods. Richard W Bailey, PMP suggests revisiting the following if you see a project going downhill based on PMBOK techniques:

- Intervention

- Assessment

- Recommendation

- Planning

- Execution

- Closure

Baily suggests using the waterfall methodology in any project recovery attempt and to look at all your project initiation documents including the project scope, charter, budget, risks and controls and use the above six steps to help you “correct incomplete or missing elements,” and “revise subsequent deliverables.” A project assessment team may be your best choice if following this PMI strategy for project recovery.

- Root Cause Strategies – A root cause analysis is another way to save a project is to examine why the project is failing. There have to be some root causes you can identify and by analyzing them, you may be able to save the project. If using a root cause method, you may be surprised to see that some of your problems seem to happen on ever project. By identifying repetitive problems, you can implement both short and long term strategies to first fix the project at hand, and then make changes to the repetitive problems for future projects.